Project Description

ARTIFICIAL PARADISES

The passion for the lost paradise, a place overflowing with beauty, harmony and exalted pleasure, is a human passion that never ceases, and is at times uncompromising to the point of violence. The amount of force we are willing to exert on ourselves and our surroundings in order to return to that same perfect place that cradles us in its bosom is apt to crush us.

Meirav Heiman returns to the lost paradises with her camera lens – places created by artificial means and made to suit the immediate, extroverted and demanding modern taste. Meirav Heiman’s paradises are tourist attractions, exotic guest rooms and garish almost toxic amusement parks in shopping malls, places where the lost paradise has become a commodity one can buy, spend a moment in, absorb and be absorbed into. “The soul of man is full of lusts: he has vast excesses of them.” Thus proclaims the French poet Charles Baudelaire,(Charles Baudelaire 1821-1867) in his book “Artificial Paradises,” dedicated to describing the intoxicating influences of hashish, opium and wine. According to Baudelaire the great passion of man is “ to be delivered, if only for a moment, from the material body in which he dwells, and ‘to attain paradise in an instant’.” The desire to reach the lost paradise by artificial means is, to a known extent, a twisted desire, but in Baudelaire’s opinion, not groundless. On the contrary “ common sense teaches us that the existence of things on this earth is only a tenuous existence, and that true reality exists solely in dreams.” If so, what is more logical than the artificial creation of a dream of happiness?

The paradises of Heiman are the industrial, capitalistic, lawful and available sequel for every consumer of Baudelaire’s paradises. Like hallucinations from hashish or opium, so too are the tourist attractions of our time – they seek to flood the visitor with an intense experience of sharpened senses and intoxicating colors. They seek to be the pivotal point that connects us to richer and more primal levels of existence, like those lost to us long ago or that exist only in our yearning imagination.

I read Baudelaire’s descriptions of the hallucinations of hashish, and am amazed to discover how they correspond with Heiman’s photographs. A “man of letters” who Baudelaire quotes tells of his experiences (according to Dori Manor, the Hebrew translator, most researchers of Baudelaire’s works are certain that the mysterious man of letters is the novelist and poet Th?ophile Gautier, while others are sure it is no other than Charles Baudelaire himself). He emerges from his home while still under the influence of the substance, and is flooded by feelings of extreme cold, which become more intense “Finally, the chill that enveloped me was so absolute, so encompassing, that all my thoughts froze, if one can say that. I became a thinking block of ice: I looked at myself as if at a statue chiseled into a large glacier; this insane illusion exalted my pride, giving me feelings of spiritual wellbeing that words do not suffice to describe.” (Ibid, page 33). Are Heiman’s photographed figures, turning their empty gaze towards the human observer, not similar to glaciers that have become part of their silent surroundings? Is the bride, standing frozen in her pure white dress like a tall and strange statue against the background of an artificial stone arch, not like a statue carved into a great glacier that is solemnly patronizing its surroundings totally?

“Hashish always requires great excesses of light,” writes Baudelaire’s man of letters. It craves after everything that illuminates, after all gold that abounds, all flowing magnificence. In short, no light is foreign to it: bright light that washes like a river, or hidden sparks that cling like straw to every point and protrusion, magnificent palace chandeliers, votive candle flames dancing in the virginal month of May or the fading pink cascades of sunset.” (Ibid, page 34).

Heiman too desires an excess of light, and it is one of the series strongest characteristics. From the depths of the corridor of the golden hall of mirrors she photographs, clear light bursts forth. Enchanted light refracts and glows in the light blue watery firmament of the mermaids’ world. It seems that light hypnotizes Heiman. Her love of color in all its hues leads her to places no less sweet and artificial than the drug induced hallucinations of Baudelaire.

Baudelaire’s man of letters, under the intoxicating influence, watches theatre and closely examines the actors. “ I saw in the observed not only the most miniscule of their props, such as the pattern on the fabrics, the seams of the costumes, the buttons etc, but also the seam line between truth and falsehood facing them, the white, blue and red and all the remaining stuff of makeup.” (Ibid, page 35). Heiman too does not attempt to convince the viewer that these are actual visions. She is aware of the fact that the sights that fascinate her are deceptive. In her work, the seam lines between truth and lies are revealed. They are the white makeup on the face of the girl at Ramat Hanetifim, the electric exit signs, the lighting elements, and the rope barriers, which the camera does not avoid. Her awareness of the artificiality of the sights she photographs is her self-awareness of the artificiality of her activity as an artist. The falseness of the situation is seen in the falsehood of the artistic action and there is no need to conceal it but just to enjoy it. The sense of intoxication of the visitor in the artificial paradises is not meant to be harmed by exposure to the artificial aspect of the situation. On the contrary, it is part of the experience, part of the hidden pleasure of control in a world created expressly to fill all desires.

Is it possible to attain real happiness through artificial paradises? Baudelaire himself is hesitant about this. “Man consequently seeks to create paradise for himself through various fermented concoctions and drinks – and thus acts like the madman who substitutes real furniture and actual gardens with an illustrated and framed d?cor,” writes the French poet. “This endless distortion of meaning is in itself that, which, in my opinion, is the cause of all sinful hyperbole.” (Ibid, page 16). Heiman too is not optimistic. Her artificial paradises empty the photographed characters of any humanity and content and turn them into part of the scenery. The characters submit to the scene, becoming part of its aesthetic weave. Their tranquility is a tranquility of imperviousness and assimilation. The colorful attractiveness of the situation does not cover up the absurdity and the alienation and even accentuates it. Her artificial paradises are devoid of an emotional aspect. In their exquisite addictive faked sensations, they are a faithful representation of the spirit of the time.

Hagar Yanai

Yediot Achronot, 2008. Translated into Hebrew: Dori Manor

Another Nature

“If there is no riddle, no mystery, don’t bother photographing it.” Sally Mann

Since completing her studies at Bezalel, Meirav Heiman has distinguished herself as a unique photographer both in her use of the language of photography and the subjects she chooses to deal with. She has an extremely personal agenda, and alternates between society, gender and culture, working with political subjects, and relating to nature and ecology. In her new series of works, Heiman deals with the human longing for nature and authenticity. She stages different scenes at commercial tourist sites in which ironically the artificial environment substitutes for reality itself. It is a journey to another nature – “Artificial Paradises,” as the name of the present exhibition proclaims.

Nature is a concept that represents all in the world not produced by man, all that is not artificial. By definition, all of mans’ products are artificial, that is, not part of the natural world. The further man moves away from nature, the more he needs to rest in the bosom of nature, which means moving away from an urban environment back to his origins and to “Mother Earth”. Evidently, even though the urban landscape supposedly provides man with all his needs, he still needs to relax occasionally in a pristine and wild place, untouched by human hand. It appears that in every age man requires a certain image of nature in order to define himself and the culture he lives in. The images or representations existing in our consciousness determine how we construct ourselves and the world. Post-modernism sees culture as that which forms our perception of nature. It is man who creates the apparent “reality” he seeks to investigate. Man is perhaps created by nature, yet it is he who now creates nature in his own image. The nature Heiman chooses to emphasize in her work is in fact a myth, and the nature-culture dichotomy conceals power conflicts and serves different ideologies.

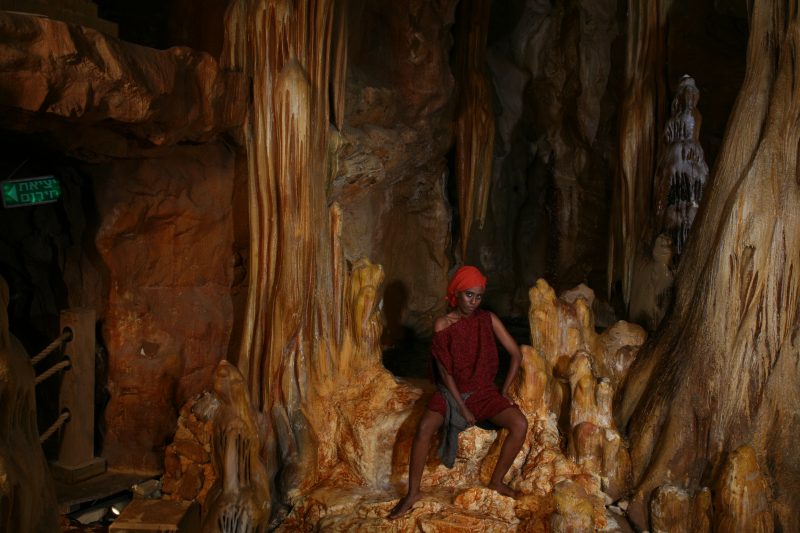

In this series Heiman describes man’s yearning for nature and the fantasy he weaves around it. Each picture creates an event specific to the people and place. The meeting between the staged and bizarre surroundings – trying to show a small piece of real life – and the staged photograph, creates mixed feelings of strangeness and intimacy. Heiman assembles her “actors” in a random fashion by advertising on the Internet or through chance encounters with them (on the way to a restroom, at a gas station and more). The fact that complete strangers are encountered in her work in momentary intimacy, staged for the camera’s eye, infuses the photographs with a sense of artificiality, and accentuates the gap between the real and the fake, while creating uneasiness and tension. This tension is noticeable in the photograph Hanoch and Michal, The Cave Suite, Moshav Hosen(2008). The exclusive guest room is designed in plastic materials as an authentic cave from the Stone Age, accessorized with all modern utilities. The surroundings are filled with candles, yet the electric lighting is blinding and prominent. The fur covering the bodies of the characters is completely synthetic. The animal bone, which the male grips forcefully in his hand like loot or a club, is also plastic. Thus a proffered experience – of “a place in which to return to the distant past and experience the innocence of human nature” – becomes an absurd clich? and anti-ecological. The plastic cave also appears in the photograph Orli, Kings City, Eilat (2008). This is a giant underground cave (one descends into it by elevator to a depth of 60 meters into the ground), which imitates a cave of stalactites and stalagmites as part of the attraction of the “Cave of Illusions” and “ the Bible Cave” at the site. At first sight the d?cor is so convincing that the fake and the real become confused. Only at second glance is it possible to notice a crooked “emergency exit” sign on the left, an electrical outlet, and a space between the decor and the floor, indicating that it’s all illusion. Ironically, these “nature” sites become a kind of reality and nature, which people are exposed to almost exclusively. The masquerade and the fabrication are obvious in the failed attempt of the characters to be wild, primitive, and to assimilate into this nature. As in Plato’s cave, so too in Heiman’s caves – what we see and understand with our senses are not real things and ideas but only a meager shadow of them.

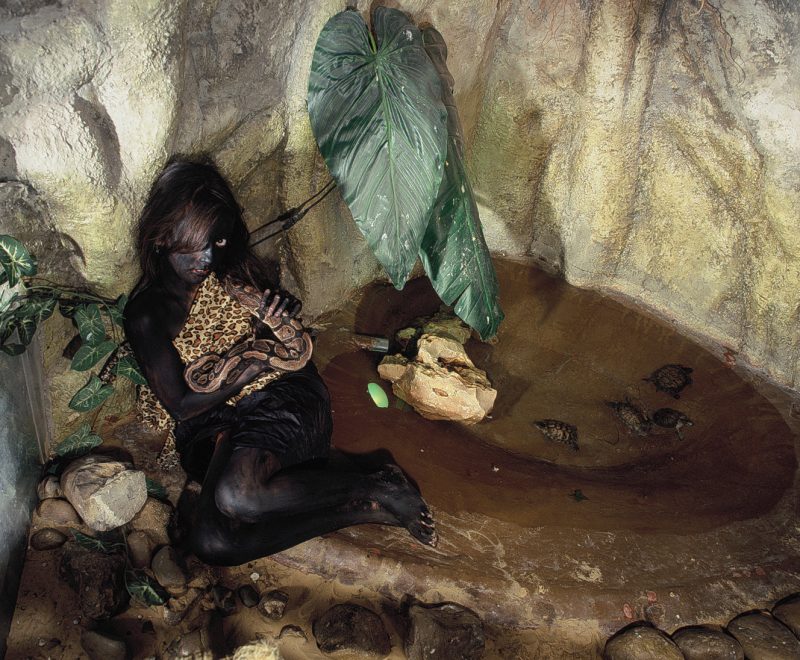

The considerable effort made by modern-western man “ to connect” with wild, prehistoric nature stands out in the photograph Eleanor, Yaarena, Arena Mall, Herzliya (2007). “Forestry” is an artificial zoo in the middle of a shopping center, without natural light or air. It imitates a tropical jungle and rain forest and contains real animals. “A wild girl” “ dark skinned’ is seated in a synthetic alcove encircled by plastic flora. She is clothed in a synthetic leopard fur and grasps a real snake, and beside her, in a pool, are four tiny water turtles, also real. The way the girl sits, the calm manner in which she grasps the snake, and the tranquil multi-colored shades of brown and green create a momentary illusion of harmony. Heiman tells of a photographic experience similar to that of Alice in Wonderland: “It was hallucinatory, in the middle of the day, in the heart of a shopping center, I opened a door, arrived at an office, opened another door and entered a forest.”

Heiman insists on staging unusual scenes, in which the characters and their humanity is palpable – whether in relation to content or whether in relation to form-color. In the work Hoffit, Orr and Tahel, Underwater Observatory, Eilat (2008), three young girls, masquerading as mermaids, sit on a rock – similar to the well-known sculpture of Edvard Eriksen in Copenhagen – but look grotesque. The distortion of their bodies, the frightening colored wigs, their theatrical pose in the artificial pool filled with stagnant water, and passivity of their postures – all these create an atmosphere that is both macabre and degrading, yet at the same time, na?ve and sad. The young girls in the photograph are aged 14-15, the age of the mermaid from the famous legend by Hans Christian Anderson (first published in 1836). The Little Mermaid is a story about tragic first love, which is unrealized, and the myth of an immortal changing into a human girl and the opposite. Heiman’s mermaids are actually ordinary young girls from Eilat who dream of beauty (their makeup is exaggerated), amuse themselves by being princesses (grasp plastic scepters and wear cheap plastic crowns on their heads), if only for a little while. The fantasy of the princess – beauty and the love of truth – here becomes tawdry and sad. The wretchedness, which represents the gap between the exciting fantasy and the disappointing reality, permeates all parts of the photograph. It is accentuated on the left where we can detect a bridge leading to the next attraction in the underwater observatory.

The mermaid myth is found in the work, Gal-Shahar, Eilat (2008), where a 10-year-old girl is seen dressed as a mermaid and made up with “glitter,” perceived from a distance as a blow to the face. It’s uncertain whether the figure is swimming or drowning, and out of balance and control. This tension creates a gap between the revealed and the concealed, between what the eye sees and what is hidden below the surface. The figure of the girl and her posture recalls the photographs of Sally Mann (Fallen Child) from 1989. In both pictures it is not clear whether the girl is in distress, although in contrast to Sally Mann’s girl, lying/falling on the ground, Heiman’s girl swims/drowns in water between heaven and earth.

An additional myth in this series is the story of Masada. Masada is a symbol and myth of heroism, deeply rooted in the consciousness of Israeli Jews and the Diaspora, and also among non-Jews ascending the rocky plateau of Masada and awed not only by the scenery and the archeological traces, but also by the story of the siege and its tragic conclusion. Heiman photographs outside at the site, between the columns, and inside, in the space of the restored synagogue at the site of the museum. She assembles a cast of Hashem the Arab-Israeli and Shai the Israeli, and in this way creates bizarre and theatrical situations connected to the local and international social experience. With great humor she confronts the past with the present, the myth of heroism and survival as a contrast to male ego and “pumping iron,” where one ritual replaces another. In fact, juxtaposing them creates a silent dialogue on issues of status, identity and honor, and at the same time, feelings of alienation, loneliness, separation and falsehood.

The historian Meron Benveniste summarized the functional importance of myths to national identity: “ Myths are the building blocks from which a nation builds its collective identity. The myth is a call to battle and a lullaby, the makeup and the mantle, the screen and the mirror, which human society uses to recruit to action, to err in dreams, to blur ugly notes, to confront a difficult reality, to draw consolation, to channel hate, to bear and to nurture his self image. Myths are not hallucinations but a mixture of real events and legend, consolidated by the glue of heroic and traumatic experiences. These are events easy to absorb and from the moment they are understood they are made more real than reality itself.”

Heiman’s method of working – creating a staged photograph – relates to the work of Canadian photographer Jeff Wall and Israeli photographer Adi Ness, who stage their scenes meticulously, down to the last detail. In contrast to them Heiman chooses to stage her work in existing set locations, and also allows their reality to penetrate, directing it in the process. “In all the works, everything starts with finding the location that for me awakens a vision and fantasy of another place. Afterwards, I looked for characters, but while doing this I was open to suggestions at the site itself. The reality penetrates the fantasy and the contrary. I don’t stage down to the last detail with a sketch, but integrate what happens to the character on site.” By design she works with a variety of non-professional “actors,” increasing the sense of fabrication at the site and the pitiable Israeli culture of leisure. Instead of the clean aesthetic manifest in the works of Wall and Ness, in Heiman we find the Israeli reality – cables and crooked signs that convey an experience of ‘”authentic artificiality.” The artificial sites are part of the goal of the so-called all-embracing culture of truth, which reaches its peak in reality shows, where the clear longing to actually touch the reality of the tangible world is shallow and staged. Jean Baudrillard claims in his book “Simulacra and Simulation” that we live in a world of reproduction and simulation whose origins are lost or did not exist at all. The tourist sites of Heiman disguise and distort reality. The more “real” they appear – the less connected they are to reality.

The size and presentation of the photographs invites the viewer to relate to them in detail and at length. They contain a revealed and hidden tension, between nature, freedom and escapism, and between culture and knowledge. Heiman’s works defy, provoke and challenge. They examine cultural, political and ecological phenomena in contemporary Israel. This humorous, embarrassing and penetrating series illustrates the pathetic nature of our existence and our need to realize impossible fantasies.

Raz Samira

“Forestry”, as Dr. Rado -responsible for the wellbeing of the animals on the site – defines it, is “the first project of its kind in the world. Throughout the world there are many large and imposing wildlife parks, yet there are no zoos in the vicinity of a shopping mall. Conventional zoos are visited by the “addicted,” animal lovers who are “crazy about” them. The idea is to bring nature to everyone. And what place is more popular than the vicinity of a shopping mall?” The place was closed in 2007

In 2007, the museum named after Yigael Yadin at the Masada Visitors Center was opened. Here findings from archeological digs are exhibited at three central points: Days of Herod, Daily Life of the Rebels on the Mountain, and Battle against the Romans.